CRD Researchers Help Model 3D Map of Adolescent Universe

International Team Demonstrates Novel Technique for Creating High-Resolution Universe Maps

October 21, 2014

By Kate Greene

Contact: cscomms@lbl.gov

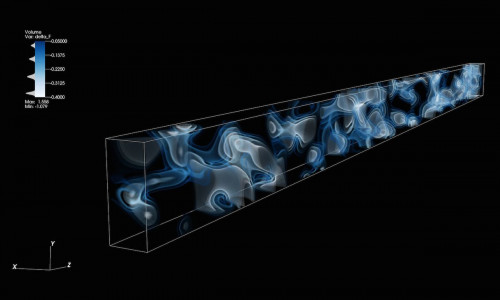

Using extremely faint light from galaxies 10.8 billion light years away, scientists have created one of the most complete, three-dimensional maps of a slice of the adolescent universe—just 3 billion years after the Big Bang.

The map shows a web of hydrogen gas that varies from low to high density at a time when the universe was made of a fraction of the dark matter we see today. It was created in part using supercomputing resources at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) by a team that included researchers from Berkeley Lab's Computational Cosmology Center (C3).

The new study, led by Khee-Gan Lee and his team at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in conjunction with researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and UC Berkeley, was published October 16, 2014 in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

3D map of the cosmic web at a distance of 10.8 billion years from Earth, generated from imprints of hydrogen gas observed in the spectrum of 24 background galaxies behind the volume. This is the first time large-scale structures in such a distant part of the Universe have been directly mapped. Credit: Casey Stark (UC Berkeley), Khee-Gan Lee (MPIA).

In addition to providing a new map of part of the universe at a young age, the work demonstrates a novel technique for high-resolution universe maps, according to David Schlegel, an astrophysicist at Berkeley Lab and study co-author. Similar to a medical computed tomography (CT) scan, which reconstructs a three-dimensional image of the human body from the X-rays passing through a patient, Lee and his colleagues reconstructed their map from the light of distant background galaxies passing through the cosmic web's hydrogen gas.

The new technique might inform future mapping projects such as the proposed Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI). Managed by Berkeley Lab, DESI has the goal of producing the most complete map of the universe yet.

“DESI was designed without the possibility of extracting such information from the most distant, faint galaxies,” said Schlegel. “Now that we know this is possible, DESI promises to be even more powerful.”

Filling in the Gaps

The first big 3D map of the universe was created using data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), which began in 1998. Over the years, the survey has provided data to make a high-resolution map of the nearby universe, within about 1 billion light years. Recent telescope upgrades have stretched our ability to map the universe to about 6 billion light years, but it’s a fairly crude map with incomplete data in some areas, according to Schlegel. The next generation of maps will come from the DESI project, scheduled to begin operation in 2018 pending funding. DESI will allow scientists to visualize 10 times the volume of SDSS and will extend about 10 billion light years away.

Beyond 10 billion light years the expectation was that the map would become sparse, said Schlegel. The reason: astronomers planned to use a familiar technique that uses the bright light of quasars, which are, unfortunately, scattered and few. The technique uses a phenomenon called Lyman-alpha forest absorption, which relies on the fact that vast clouds of hydrogen exist between Earth and distant quasars and galaxies. At a certain distance, as measured by the red shift of the light, astronomers can determine the density of hydrogen, based on the absorption of quasar light. The problem is that this only provides information about the presence of hydrogen along the line of sight, not over a larger volume of space.

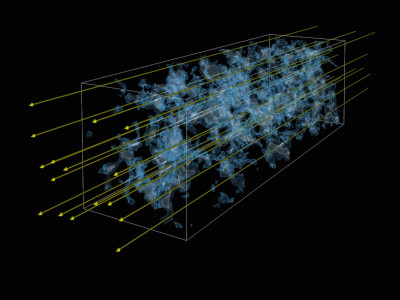

“It’s a pretty weird map because it’s not really 3D,” explained Schlegel. “It’s all these skewers; we don’t have a picture of what’s between the quasars, just what’s along the skewers.” The researchers believe their new technique, which uses the faint light of numerous distant galaxies instead of that of sparse quasars, can fill in the gaps between these skewers.

Artist’s impression illustrating the technique of Lyman-alpha tomography: as light from distant background galaxies (yellow arrows) travel through the Universe towards Earth, they are imprinted by the absorption signatures from hydrogen gas tracing in the foreground cosmic web. By observing a number of background galaxies in a small patch of the sky, astronomers were able to create a 3D map of the cosmic web using a technique similar to medical computed tomography (CT) scans. Credit: Khee-Gan Lee (MPIA), Casey Stark (UC Berkeley)

Cosmological Cartography

Before this study, no one knew if galaxies further than 10 billion light years away could provide enough light to be useful, Schlegel said. But earlier this year, the team collected four hours of data on the Keck-1 telescope during a brief break in cloudy skies.

“It turned out to be enough time to prove we could do this,” Schlegel said.

Of course, the galaxies’ light was indeed exceedingly faint. In order to use it for a map, the researchers needed to develop algorithms to subtract light from the sky that would otherwise drown out the galactic signals. Schlegel developed the algorithm to do this, while Casey Stark—a UC Berkeley astrophysics graduate student who works in Berkeley Lab’s Computational Research Division and in the C3—and Martin White, a UC Berkeley physicist and theoretical cosmologist, developed a code dubbed “Dachshund” that uses a Wiener filter signal processing technique to reconstruct the 3D field from which the signal is drawn.

Stark and White used large cosmological simulations run at NERSC to construct mock data and to test the robustness of the maps. Running mock reconstructions on NERSC's Edison system was a crucial step in validating the method and code, Stark emphasized. After optimizing the tomography code on Edison, he and White collaborated with Lee to process the data for the Astrophysical Journal Letters study.

"The signal processing technique we used is much like what you would do for a CT scan, where you have a sparse sampling of a field and you want to fill in the gaps. In our case, we observe the absorption along lines to distant galaxies and then infer the amount of absorption between the lines," Stark explained. "The technique is simple, but it's an expensive computation. Fortunately, we realized we could simplify the computations by tailoring them to this particular problem and thus use much less memory. With that simplification, the code is very easy to parallelize."

Because the project was a proof-of-concept, the researchers are planning future Keck-1 telescope time to extend the volume of space they map.

“This technique is pretty efficient, and it wouldn’t take a long time to obtain enough data to cover volumes hundreds of millions of light years on a side,” said Khee-Gan Lee.

Read the news release from Max Planck Institute for Astronomy here.

About Berkeley Lab

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 16 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.