Supernovae of the Same Brightness, Cut from Different Cosmic Cloth

A historic observation of a rare Type 1a supernova

August 23, 2012

By Linda Vu

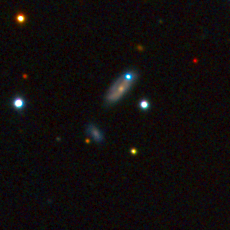

The supernova PTF 11kx can be seen as the blue dot on the galaxy. The image was taken when the supernova was near maximum brightness by the Faulkes Telescope North. The system is located approximately 600 million light years away in the constellation Lynx. Image Credit: BJ Fulton (Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network)

Exploding stars called Type 1a supernovae are ideal for measuring cosmic distance because they are bright enough to spot across the Universe and have relatively the same luminosity everywhere. Although astronomers have many theories about the kinds of star systems involved in these explosions (or progenitor systems), no one has ever directly observed one—until now.

In the August 24 issue of Science, the multi-institutional Palomar Transient Factory (PTF) team presents the first-ever direct observations of a Type 1a supernova progenitor system. Astronomers have collected evidence indicating that the progenitor system of a Type 1a supernova called PTF 11kx contains a red giant star. They also show that the system previously underwent at least one much smaller nova eruption before it ended its life in a destructive supernova. The system is located 600 million light years away in the constellation Lynx.

By comparison, indirect observations of another Type 1a supernova progenitor system (called SN 2011fe, conducted by the PTF team last year) showed no evidence of a red giant star. Taken together, these observations unequivocally show that just because Type 1a supernovae look the same, that doesn’t mean they are all born the same way.

“We know that Type 1a supernovae vary slightly from galaxy to galaxy, and we’ve been calibrating for that, but this PTF 11kx observation is providing the first explanation of why this happens,” says Peter Nugent, who leads the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory's (Berkeley Lab's) Computational Cosmology Group and is a co-author on the paper. “This discovery gives us an opportunity to refine and improve the accuracy of our cosmic measurements.”

“It’s a total surprise to find that thermonuclear supernovae, which all seem so similar, come from different kinds of stars,” says Andy Howell, a staff scientist at the Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network (LCOGT) and a co-author on the paper. “How could these events look so similar if they had different origins?”

A One in a Thousand Discovery, Powered by Supercomputers

Artist's conception of a binary star system that produces recurrent novae, and ultimately, the supernova PTF 11kx. A red giant star (foreground) loses some of its outer layers through a stellar wind, and some of it forms a disk around a companion white dwarf star. This material falls onto the white dwarf, causing it to experience periodic nova eruptions every few decades. When the mass builds up to near the ultimate limit a white dwarf star can take, it explodes as a Type Ia supernova, destroying the white dwarf. (Credit: Romano Corradi and the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias)

Artist's conception of a binary star system that produces recurrent novae, and ultimately, the supernova PTF 11kx. A red giant star (foreground) loses some of its outer layers though a stellar wind, and some of it forms a disk around a companion white dwarf star. This material falls onto the white dwarf, causing it to experience periodic nova eruptions every few decades. When the mass builds up to the near the ultimate limit a white dwarf star can take, it explodes as a Type Ia supernova, destroying the white dwarf. (Credit: Romano Corradi and the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias)

Although Type 1a supernovae are rare, occurring maybe once or twice a century in a typical galaxy, Nugent notes that finding a Type 1a progenitor system like PTF 11kx is even more rare. “You maybe find one of these systems in a sample of 1,000 Type 1a supernovae,” he says. “The Palomar Transient Factory Real-Time Detection Pipeline was crucial to finding PTF 11kx.”

The PTF survey uses a robotic telescope mounted on the 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope at Palomar Observatory in southern California to scan the sky nightly. As the observations are taken, the data travels more than 400 miles via high-speed networks—including the National Science Foundation’s High Performance Wireless Research and Education Network and the Department of Energy’s Energy Sciences Network (ESnet)—to the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), located at Berkeley Lab. There, the Real-time Transient Detection Pipeline uses supercomputers, a high-speed parallel filesystem and sophisticated machine learning algorithms to sift the data and identify events for scientists to follow up on.

According to Nugent, the pipeline detected the supernova on January 16, 2011. He and UC Berkeley postdoctoral researcher Jeffrey Silverman immediately followed up on the event with spectroscopy observations from the Shane telescope at the University of California’s Lick Observatory. These observations revealed incredibly strong calcium signals in the gas and dust surrounding the supernova, which is extremely unusual.

The signals were so peculiar that Nugent and his UC Berkeley colleagues, Alex Filippenko and Joshua Bloom, triggered a Target of Opportunity (ToO) observation using the Keck Telescope in Hawaii. “We basically called up a fellow UC observer and interrupted their observations in order to get time critical spectra,” Nugent explains.

From the Keck observations, astronomers noticed that the clouds of gas and dust surrounding PTF 11kx were moving too slowly to be coming from the recent supernova, but moving too quickly to be stellar wind. They suspected that maybe the star erupted, or went nova, previously, propelling a shell of material outwards. The material, they surmised, must be slowing down as it collided with wind from a nearby red giant star. But for this theory to be true, the material from the recent supernova should eventually catch up and collide with gas and dust from the previous nova. That’s exactly what the PTF team eventually observed.

In the months following the supernova, the PTF team watched the calcium signal drop and eventually vanish. Then, 58 days after the supernova went off, Berkeley Lab Scientist Nao Suzuki, who was observing the system with the Lick telescope, noticed a sudden, strong burst in calcium coming from the system, indicating that the new supernova material had finally collided with the old material.

“This was the most exciting supernova I’ve ever studied. For several months, almost every new observation showed something we’d never seen before,” says Ben Dilday, a UC Santa Barbra postdoctoral researcher and lead author of the study.

A New Kind of Type 1a Supernova

According to Dilday, it is not unusual for a star to undergo nova eruptions more than once. In fact, a “recurrent nova” system called RS Ophiuchi exists within our own Milky Way Galaxy. Located about 5,000 light years away, the system is close enough that astronomers can tell that it consists of a compact white dwarf star (the corpse of a sun-like star) orbiting a red giant. Material being blown off the red giant star in a stellar wind lands on the white dwarf. As the material builds up, the white dwarf periodically explodes, or novas, in this case about every 20 years.

Astronomers predict that in recurring novas, the white dwarf loses more mass in the nova eruption than it gains from the red giant. Because Type 1a supernovae occur in systems where a white dwarf accretes mass from a nearby star until it can’t grow any further and explodes, many scientists concluded that recurrent nova systems could not produce Type 1a supernovae. They thought the white dwarf would lose too much mass to ever become a supernova. PTF 11kx is the first observational evidence that Type 1a supernovae can occur in these systems.

“Because we’ve looked at thousands of systems and PTF 11kx is the only one that we’ve found that looks exactly like this, we think it is probably a rare phenomenon. However, these systems could be somewhat more common, and nature is just hiding their signatures from us,” says Silverman.

The Palomar Transient Factory's Real-Time Detection Pipeline is made possible with support from the DOE Office of Science’s Advanced Scientific Computing Research program, NASA, and the National Science Foundation.

About Berkeley Lab

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 16 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.